It was Saturday morning, and I hadn’t had any coffee. It is no wonder I was surprised to hear these words coming from our kitchen radio:

He who wants to withdraw from danger will lose his life. But the person who gives himself to the service of others will be like a grain of wheat that falls to the ground and dies — but only apparently dies, for by its death, its wasting away in the ground, a new harvest is made.

“What? Who was that?” I stuttered to my husband, astonished to hear a sermon coming from the NPR airwaves. “Romero,” he replied, “The Pope is going to make him a saint.”

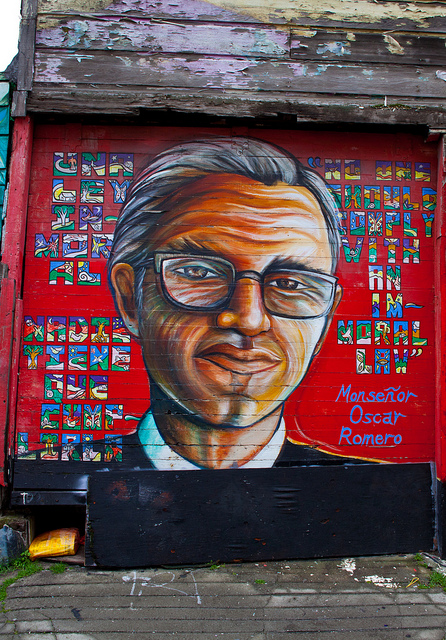

And in this way I was re-introduced to Archbishop Oscar Romero, the Salvadoran priest and prophet who confronted the violent injustice and oppression that was so rampant in El Salvador in the late 1970s. I was a bit embarrassed that couldn’t remember much more (it had been 15 years since I’d seen the “Romero” movie) so I took to the Internet.

In my research I learned that then-bishop Romero was chosen for archbishop in 1977. For many years the church and the government had worked hand-in-hand to protect the status of the rich and powerful in El Salvador, and Romero was considered a conservative, a harmless bookworm. The socially-active clergy were crushed by Romero’s appointment.

But Romero had a good friend among the progressives, Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande. Father Grande was an ‘agitator.’ He organized landless peasants, and protested the increasingly violent tactics of the Salvadoran elite. He also prodded Romero to re-consider his responsibilities to a helpless and harassed flock. Less than a month after Romero’s appointment as archbishop, Father Grande was assassinated.

Father Grande’s death was catalytic for Romero. The next morning he began to challenge the status quo that he had previously upheld, and quickly became a voice-and priest-to the marginalized poor of El Salvador. Every Sunday his homilies were broadcast on the radio, and after giving a charge for God’s kingdom to come on earth as in heaven, Romero would read the names of the murdered and ‘disappeared’. He received threats, but refused protection, saying that he could not take accept security that was denied to his flock.

Three years after the death of his friend, on the evening of March 24, 1980, Romero was also assassinated, moments after he preached

He who wants to withdraw from danger will lose his life. But the person who gives himself to the service of others will be like a grain of wheat that falls to the ground and dies — but only apparently dies, for by its death, its wasting away in the ground, a new harvest is made.

In retrospect, we can apply these words to Father Romero’s imminent death. Certainly Romero knew that his life was in grave danger, certainly he knew that the death squads would come for him too. He was “giving himself to the service of others”, and in doing so, he had made powerful enemies.

But I wonder if Romero thought of Father Grande that night.

Isn’t this the way it works? Father Grande’s sacrifice was the seed for Romero’s service, and in turn, Romero’s death created a new harvest. Last week’s move by the Vatican only confirms what is already known: the seeds of sacrifice multiply and grow.

And as they shouted in the streets of El Salvador last Tuesday, “Bendito sea Dios!”

For further reading:

One of Romero’s final sermons, http://www.haverford.edu/relg/faculty/amcguire/romero.html

Article about the Pope Francis’ announcement last Tuesday, http://www.npr.org/blogs/parallels/2015/02/05/384067797/decades-after-his-murder-an-archbishop-is-put-on-path-to-sainthood

And… a (lengthy) paper about the relationship between Father Romero and Father Grande, http://www.academia.edu/8605676/Rutilio_Grande_S.J._Evangelizing_Exemplar_for_Archbishop_Oscar_Romero

Jen Pelling is a PTS alumna on the winding path of life-after-seminary. She received her Master of Divinity in 2010, and is an elder at Valley View Presbyterian Church in Pittsburgh, Pa. She writes and edits for the You Are Here blog (www.youareherestories.com), freelances in her “free” time, works with other people’s children in various settings, and mothers her own two daughters with joy and frequent prayers for patience. Both she and her husband, Kendall, can walk to work in less than 15 minutes; he works in the residential arm of a community development corporation and she works two blocks away as a communications associate for CCO campus ministry.

That’s a smart way of thkniing about it.