One of the best things about attending a small Christian college in the Midwest was worshiping in a local congregation on Sunday alongside professors and university staff, factory workers and business owners, and even the university president. No matter who someone was at the university or in town during the week, in worship we were all equals.

On Sundays, I talked with professors about football or our families. Occasionally, I would sign up to be liturgist or a communion server, meaning I sometimes led my professors and the university president in liturgy and served them communion! A similar dynamic exists in Pittsburgh Seminary’s Hicks Chapel when gathering for mid-week worship among students, faculty, and staff.

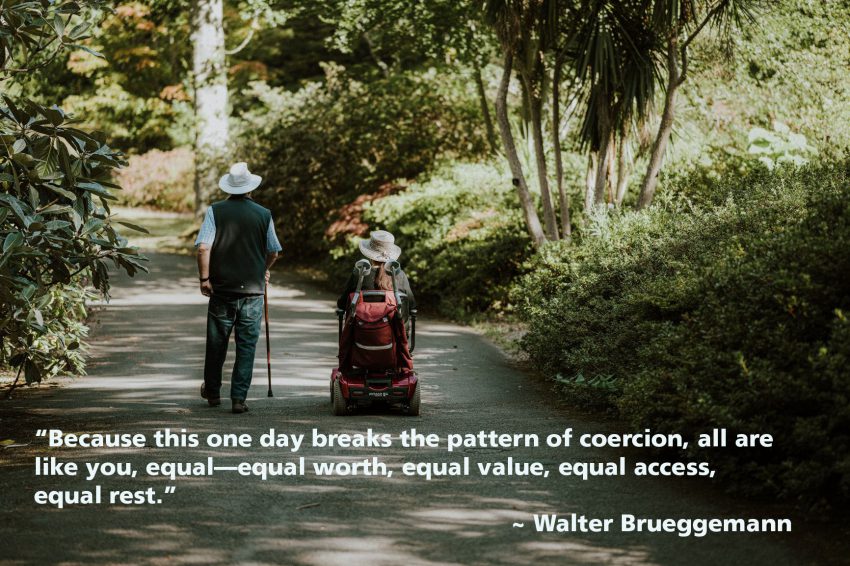

Christian worship is a sacred time where our roles from the rest of the week no longer matter. Teachers and students sit together in the pew. Managers receive communion from their employees. Organizational charts cease to exist. Regardless of income or ability, we all sing the same songs and pray the same prayers. Social standing evaporates when we enter the sanctuary and face the cross together. The fourth of the Ten Commandments—“Observe the Sabbath day and keep it holy”—changes everything.

The Fourth Commandment

According to Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann in his book Sabbath As Resistance: Saying No to the Culture of Now, the Israelites of the Old Testament were enslaved in Pharaoh’s system of demanding production quotas, and in this system neighbors could not be loved but only viewed as threat and competition. But the fourth commandment imagines Sabbath as, among other things, a call to equality.[1]

In the version of the Ten Commandments found in Deuteronomy 5, the Sabbath is a rest day for everyone: all genders, all ages, all members of society, free or enslaved, Israelites and foreigners, and even oxen, donkeys, and all livestock. All beings need rest, all beings deserve rest, and all beings shall receive rest, according to the Lord. The fourth commandment is a radical command to set aside production and labor so that all may worship together.

Rest that Equalizes

Sabbath is meant to level the playing field. It is something all people should receive, and yet all people don’t.

Brueggemann says, “Deuteronomy identifies widows, orphans, and immigrants as needy members of society who are without protected rights.” Observing Sabbath includes protecting equal rights for all people to observe it. He goes on to say: “It is no stretch at all to see that on Sabbath day these vulnerable, exposed neighbors shall be ‘like you,’ peaceably at rest.”[2]

A Disruption of the Status Quo

Civil society tends to determine a person’s worth and significance by production and consumption. But we differ in our abilities to produce and consume due to talent, physical or mental ability, and access to resources.

Sabbath breaks that. When everyone has the chance to rest, and everyone can worship together, then we begin to foster an environment of security, respect, and dignity that gives equal worth to all people. Whatever our civil relationships are to each other during the week, in worship we recognize Sabbath as a great equalizer, where all are equally at rest and so all are equal.

The following words from Brueggemann may be used as a litany in worship this Sunday or at another time:

On the Sabbath:

You do not have to do more.

You do not have to sell more.

You do not have to control more.

You do not have to know more.

You do not have to have your kids in ballet or soccer.

You do not have to be younger or more beautiful.

You do not have to score more.

Because this one day breaks the pattern of coercion, all are like you, equal—equal worth, equal value, equal access, equal rest.[3]

Author: The Rev. Erik Hoeke is a writer at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church with 14 years of pastoral ministry experience in Southwestern Pennsylvania.

Author: The Rev. Erik Hoeke is a writer at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and an ordained minister in The United Methodist Church with 14 years of pastoral ministry experience in Southwestern Pennsylvania.

[1] Brueggemann, Walter. Sabbath as Resistance: Saying No to a Culture of Now. Van Haren, 2017. p. 5.

[2] Ibid., pp. 44-45.

[3] Ibid., pp. 40-41.

I really love this, and Brueggemann as well (it calls me to a new way of seeing Sabbath!) I can’t number how many of the 24 or 25 Labor Day Sunday’s I preached that I used this text in combination with Genesis 2:4 (focus: if God rested, what does it say about us that we think we don’t need rest? or that the world will fall apart if I take a time of rest?) I’m also not sure where I read it, but make total disclaimer that the notion is not mine: that there is a huge significance in that we are called ‘human BEings’ as opposed to ‘human DOings’.

I only wish that I’d been more aware of the justice of equality aspect of Sabbath back then.

Thank you for at least pointing it out now!

I wonder what would happen if we just didn’t shop on Sunday? No groceries, no take out, no online orders…all things that ask others to work on the Sabbath.