Earlier this academic year, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s American Religious Biography class studied biographical accounts of seven women and men whose lives spanned the centuries from the colonial era through the 20th century. After digging deeply into the historical accounts of those Christian figures, students reflected on what insight each narrative might have for modern Christians, asking What we can learn from the past to inform modern lives of faith? The blog below is the first in a four-part series of reflections by students in this course taught by the Rev. Dr. Heather Vacek.

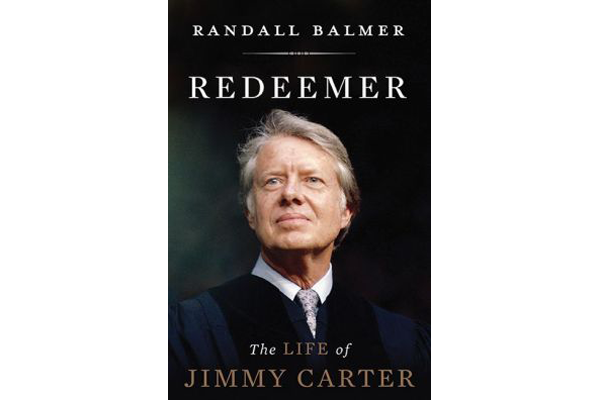

Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter by Randall Balmer is a biography of the 39th President of the United States and details the former President’s biblical theology. The book charts Carter’s religiosity as a “means for understanding his life and character” (xxvi). Religion, notably evangelicalism, played a role in the victory and defeat of Carter. Additionally, Balmer traces post-presidency Carter and his many humanitarian endeavors. The book also reveals the history of the Moral Majority and Religious Right, groups that are often accused of influencing policies that oppose the fundamental rights of minorities. Carter became their first victim.

Carter was born in 1924 and was born again in 1935.He graduated from the Naval Academy and married the former Rosalynn Smith, raising four children. He left the Navy and successfully took over the family business, but longed for a political career. He was elected to the Georgia State Senate in 1962. His mantra became Reinhold Niebuhr’s maxim: “The sad duty of politics is to establish justice in a sinful world” (20). Perhaps it should have read “politics is a sinful world,” when Carter announced his second run for governor in 1970.

Although Carter had recommitted his life to Christ, he had been stung by defeat in the 1966 gubernatorial race. During his 1970 run he courted segregationists and endorsed Lester Maddox, an axe wielding racist, as his lieutenant governor. He had compromised his Christian identity for political glory. But with his win he was able to make many reforms and improve race relations. And he began to state openly, “I am a born again Christian” (40). A new movement was reawakening after decades of dormancy.

Jimmy Carter shared the ideals of progressive evangelicalism: “equality for women and minorities, economic justice, and repudiation of militarism” (45). Carter was in the right place at the right time—after Nixon, America needed a president they could trust. He was elected to the presidency in 1976 and moved forward with his campaign promises: addressing the energy crisis, human rights, transferring the Panama Canal, reaching the Camp David accord, and reducing the proliferation of nuclear arms. All was good—or was it? Fundamentalists who strived for a “Christian nation” were about to pounce on Carter for his perceived weakness on foreign policy and “moderate” views on social issues.

Jerry Falwell, Pat Robertson, Bob Jones, Anita Bryant, and Billy Graham were determined not to let Carter have a second term. Political operative Paul Weyrich found that abortion, homosexuality, and especially desegregation could be key factors conservative evangelicals could use to destroy Carter, who proved unwilling to step in line with their proposed policies. These Christians decried that their institutions were denied tax exemptions for refusing to admit blacks. They opposed equal rights for women, discrimination protection for homosexuals, and supported a constitutional amendment to ban abortions. Conservatives framed the issues in terms of religious freedom, not any sort of discrimination (104). But these were not the only problems Carter faced.

The 1979 Iran hostage crisis “cast a pall over everything” Carter did (128). An attempt to free the hostages ended in disaster. All other candidates suddenly professed their affiliation with evangelicalism. The Religious Right constantly blasted Carter with sharp political rhetoric. It was like the world had turned upside down and shaken out all the good. “Free market capitalism, disregard of human rights and military might” seemed to be the songs of the day (155). Fundamentalists and evangelicals were successful in defeating a true evangelical. Coincidentally, 15 minutes after Reagan was sworn in as president, the American hostages were freed in Iran. The world had become a stage for Reagan.

Jimmy Carter has managed to redeem himself after life in the White House, whether it be by establishing the Carter Center, doing work with Habitat for Humanity, or teaching Sunday school. Carter was also awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Now in his 90s, he continues doing God’s work. Carter stated, “Piety alone isn’t sufficient- followers of Jesus must live out their convictions with acts of charity” (162). As President Carter has battled his most formidable foe, cancer, I hold him in my thoughts and prayers and rejoice in his recent announcement of effective treatment.

All citations taken from: Balmer, Randall Herbert author. Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2014.

The full reading list for the Fall 2015 American Religious Biography course included: Catherine Brekus, Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (2013), John Wigger, American Saint: Francis Asbury and the Methodists (2009), Jon Sensbach, Rebecca’s Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World (2005), Richard S. Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (2008), Matthew Avery Sutton, Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America (2007), Sarah Azaransky, The Dream is Freedom: Pauli Murray and Democratic American Faith (2011), Randall Balmer, Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter (2014). In addition, readers interested in the role of history in the life of faith might enjoy: Margaret Bendroth, The Spiritual Practice of Remembering (2013).

Lisa Steimer is a senior MDiv student at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.

3 thoughts on “Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter”