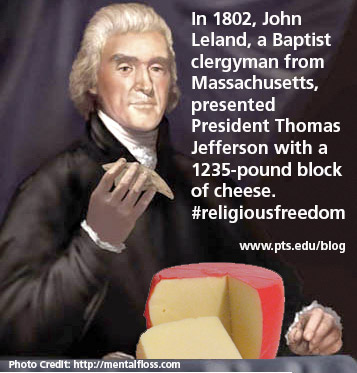

In 1802, John Leland, a Baptist clergyman from Massachusetts, presented President Thomas Jefferson with a 1235-pound block of cheese. New England believers commissioned that “Mammoth Cheese” to celebrate Jefferson’s election. The gift also signaled appreciation for the President’s support of religious freedom.

It’s hard to miss the irony in a member of the clergy bestowing such a pungent blessing on a president’s work to legislate separate spheres of church and state or in the fact that Leland accepted Jefferson’s invitation to preach to Congress a few days later. A sermon given on the floor of Congress may fit within the bounds of religious freedom, but it hardly keeps church and state at arm’s length.

In the middle of this fall’s election season, does history offer any insight for voters who count themselves part of faith traditions? Hopefully.

While at least a few Baptists in the young nation approved of Thomas Jefferson’s policies and the country’s direction, a recent study showed that fewer than 30 percent of Americans are satisfied with the way things are going in the country today. Widespread dissatisfaction, however, fails to signal broader agreement. Issues including definitions of marriage, interpretations of science, and the allocation of government spending divide voters, deeply. Divisions prompt citizens to seek companionship with likeminded Americans. Another recent study highlighted the divide between citizens by studying their media habits: “When it comes to getting news about politics and government, liberals and conservatives inhabit different worlds.”

To be sure, people of faith are among the nation’s dissatisfied citizens, but they are also among the country’s polarized constituencies.

Perhaps the relationship between religion and politics in the U.S. seems like it should be straightforward. The historical record, though, demonstrates that the interaction between faith and politics has been filled with irony and complexity. Rarely have American Christians agreed about the right relationship between church and state. Nor have they found common ground about the priority of issues or the right stance for believers. A few examples highlight diverse reactions.

In Jefferson’s day, not all Christians shared the Baptists’ love for the President. The Dutch Reformed minister, William Linn, feared that what he viewed as Jefferson’s lack of orthodox Christian beliefs would ruin the new nation. Linn spoke boldly against the founding father’s candidacy.

Later that century, Christians reacted differently to the nation’s moral debates and laws. The legal enslavement of African Americans prompted the antebellum Quaker abolitionist Angelina Grimké to proclaim, “wicked laws ought be no barrier in the way of [Christian] duty.” Alternately, her southern contemporary, the Presbyterian minister George Armstrong urged obedience to the law with his assertion that “the question of emancipation” belonged “to the State, and not the Church, to settle.”

Whether to engage in the political realm proved a point of consideration in the following century too. The evangelist Billy Graham interacted with political leaders throughout his career, but also recommended Christians “devote themselves to missionary work and not get distracted by undue attention to political and social issues.” Not all agreed.

Over the past few decades, many believers – clergy and laity alike – have taken part in protests hoping to spark change in the political realm that span a wide variety of issues. Marches and demonstrations in Washington D.C., and other cities weighed in on Civil Rights, legalized abortion, and the Equal Rights Amendment. More recently, people of faith rallied around Moral Monday demonstrations in North Carolina, joined protesters in New York to raise awareness about climate change, and showed outrage at the shooting death of Michael Brown and police action in Ferguson, Mo. Christians turned their energies toward a variety of political issues and, at times, took opposing sides in protests. Rooted in faith convictions, each of those efforts sought to witness to and press for an alternate future.

Given a diversity of historical responses, how might Christians think about their vote in upcoming elections? It is clear that faith convictions shape action in the world. History makes evident, however, that it is hard to predict or define one, lone, Christian response. Deep divisions persist as Christians engage politically. Such divides often prove severe enough that they disable productive conversation, and for Christians, inhibit the unity of the church and our witness to the world.

Instead of viewing division as inevitable, believers might try to bridge the deep divides, or at least seek genuine conversations across them. Finding ways to be in conversation – even if not agreement – with voices (past and present) that differ might yield insight and sympathy and strengthen Christian witness. Such conversations might prompt the formation of productive communities of discernment as believers navigate the modern world.

As a historian of American Christianity, I commend the study of history as a helpful background as we consider how faith shapes politics in upcoming elections. Wade through the diversity of beliefs of the nation’s founders with John Fea’s Was America Founded as a Christian Nation. Or, for those interested in more recent conversation partners, jump into the fray of Christianity and politics in the twentieth century by travelling through the development of conservative Christian engagement in the political realm with Daniel K. Williams’s God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right or trace the alternate witness of socially minded Protestants in David R. Swartz’s Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism.

Better yet, believers might talk face-to-face with someone they disagree with about an election or issue – and not just other Christians engaged with others in the community. There is value in relationship. There is wisdom to be gained by listening to voices from the past and the present and working to see if we can understand the logic behind one another’s convictions. It may not change our votes, but relationship and conversation just might change the world.

- For more on John Leland, see Nathan O. Hatch’sThe Democratization of American Christianity,pp. 93-101.

- For more on William Linn and Thomas Jefferson, see John Fea’s Was America Founded as a Christian Nation, pp. 6-7.

- For Billy Graham quotation, see Curtis J. Evans, “White Evangelical Protestant Responses to Civil Rights Movement,” Harvard Theological Review 102, 2 (2009): 261.

The Rev. Dr. Heather Hartung Vacek is assistant professor of church history at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Her research focuses on the historical relationship between Christian belief and practice in the American context. Dr. Vacek’s most recent work explores Protestant reactions to mental illnesses from the colonial era until the 21st century.