Tensions were high and hope was scarce during the summer of 2020. Protests were ongoing nationally, triggered by the senseless killing of unarmed African Americans—George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minn. and Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky.

However, on June 5, 2020, I was awakened by special news coverage of a mural commissioned by Mayor Muriel Bowser in Washington, D.C. Upon seeing the mural for the first time, I saw the epitome of contextual art. Nothing was more beautiful at that moment than those bold yellow letters painted to remind the world that the lives of my village, sisters, brothers, mothers, fathers, and all my folk mattered. Without the excruciating pain of racism and othering in America, I would not know the beauty and unbridled joy of seeing a public demonstration, a signature on a city street, to remind me that my life matters amid forces, powers, systems, and voices who have explicitly communicated with their actions that I do not.

Speaking That Moves Beyond Words

Folk preaching is contextual art that evokes emotions and communicates meanings that cannot be captured in words, tropes, and phrases. Folk preaching is so much more than words and rhetorical devices. By folk preaching, I am referring to sermons that originated in the earliest period in African American preaching, 1750-1865, referenced by Frank A. Thomas, Martha Simmons, Henry H. Mitchell, O.C. Edwards, and others as the “folk period” in the history of African American preaching. In my work, I interpret the speeches of Maria W. Stewart as folk sermons.

Maria W. Stewart: Orator, Advocate, and Apologist for Women Preachers

Maria W. Stewart was born free in 1803 in Hartford, Conn. Simmons and Thomas state that she married James W. Stewart in 1826 in Boston and was widowed after three years of marriage. Stewart considered herself an advocate for liberation, social change, and women’s flourishing. She also believed in defending her views and theological statements regarding sin, salvation, regeneration, and redemption.

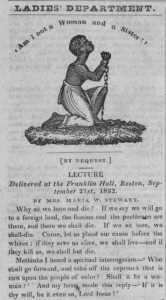

Stewart delivered the speech “What If I Am a Woman?” Sept. 21, 1833, in favor of women’s rights and agency. In her speeches, she advocates for Black uplift and equality. Few scholars of her work would disagree that Stewart emphasized “Black women’s survival, moral purity, and social advancement.”[1] Scholars such as Simmons and Thomas note that she “believed religion and Black self-determination would lift African Americans from degradation.[2] Stewart believed that God sanctioned her call as a preacher. Her meditation, “What If I Am a Woman?” “has been identified as her farewell address to Boston. Thus, it included her apologetics for women preachers.”[3]

The Future of Rhetorical Theology: Stewart’s Legacy in Folk Preaching Today

Maria W. Stewart’s 1832 speech made clear the valuable function that folk homiletics can serve in the future of rhetorical theology. Rhetorical theology asserts that theology is an argument of persuasion, focusing on the method of persuasion used by the rhetor. Persuasion intends to move the audience within a particular context. “Rhetorical theology does not only investigate the truth of a doctrine. Rhetorical theology is concerned with the practical implications of doctrine within a context.”[4]

Rhetorical theology does not only investigate the truth of a doctrine. Rhetorical theology is concerned with the practical implications of doctrine within a context.

There is much more that can be said about the speeches of Maria W. Stewart, in addition to her use of rhetorical theology and of Black uplift motifs. “What If I Am a Woman?” is one example of how the speeches of 19th century African American women revealed valuable techniques for understanding contemporary theology and folk homiletics. By considering Stewart’s speeches through the lens of folk homiletics, we gain a more complex understanding of the history of Africana folk preaching and how the folk ethic has always guided Black orators like Stewart. Like the Black Lives Matter mural on 16th Street NW, Stewart’s rhetoric functioned as her signature on a city street to remind her audiences that their dignity, flourishing, and lives mattered to God. Considering our current social climate, it is clear that this message is still vitally needed today. Now, it is our turn to take up Stewart’s legacy and remind those in our society’s margins that they matter to God.

[1] Martha J. Simmons and Frank A. Thomas, Preaching with Sacred Fire: An Anthology of African American Sermons, 1750 to the Present (New York, and NY: W.W. Norton, 2010), 203.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Andre E. Johnson, “The Prophetic Persona of James Cone and the Rhetorical Theology of Black Theology,” Black Theology 8, no. 3 (September 2010): 282.

The Rev. Dr. Jennifer Carner is director of the Preaching in a Post-Christian Age Initiative and visiting assistant professor of preaching at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Her primary areas of interest include African American sacred proclamation and the rhetoric of social movements, folk preaching and the practice of a folk ethic in preaching, histories of homiletic theory, and histories of American preaching. She has served as assistant professor of religion at Barry University and ministered at The Greater Travelers Rest Baptist Church, Atlanta, Ga., where she served as senior manager, executive pastor, preaching assistant, membership care pastor, content creator, and global operations manager. Dr. Carner holds a B.S. in Christianity/theology from Mercer University, an M.Div. from Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, and a Ph.D. in African American preaching and sacred rhetoric from Christian Theological Seminary.

The Rev. Dr. Jennifer Carner is director of the Preaching in a Post-Christian Age Initiative and visiting assistant professor of preaching at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. Her primary areas of interest include African American sacred proclamation and the rhetoric of social movements, folk preaching and the practice of a folk ethic in preaching, histories of homiletic theory, and histories of American preaching. She has served as assistant professor of religion at Barry University and ministered at The Greater Travelers Rest Baptist Church, Atlanta, Ga., where she served as senior manager, executive pastor, preaching assistant, membership care pastor, content creator, and global operations manager. Dr. Carner holds a B.S. in Christianity/theology from Mercer University, an M.Div. from Emory University’s Candler School of Theology, and a Ph.D. in African American preaching and sacred rhetoric from Christian Theological Seminary.

1 thought on “Signatures on City Streets—Maria W. Stewart, Contextual Art, and “What If I Am a Woman?””