Three years ago on a Saturday afternoon in Advent I was frantically rewriting the beginning of my sermon for the next morning. The day before a gunman had entered Sandy Hook Elementary School and killed 20 children and six adults.

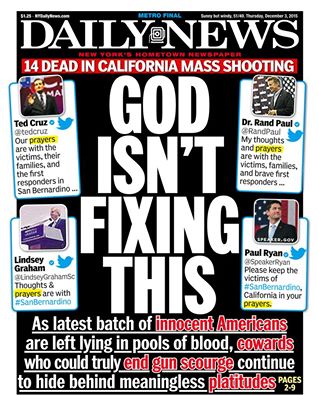

This Advent pastors are drafting sermons after another massacre. And many will try to address what is on people’s minds after the provocative headline on the front page of the New York Daily News: “God Isn’t Fixing This.”

The headline intends to point to the hypocrisy of politicians who offer “thoughts and prayers” while opposing laws that might prevent some of these massacres. But people without the power to pass laws also feel challenged by the headline. What should we believe or say about God’s relationship to these events?

Sometimes it’s easier for me to know what I don’t believe. But here are three things I do believe and would be willing to say:

God did not cause this. After a massacre or natural disaster, we can count on someone—usually a religious leader with a platform—saying the incident is part of God’s mysterious plan. Perhaps some people take comfort in this. I don’t. I can confidently tell my children, and I would happily tell a congregation: God did not will this massacre.

Death is an interloper, especially these violent, untimely deaths. Death is not God’s will. Someday there might be time for theological debate about God’s relationship with evil, the place of death in God’s plan, or what it even means to say God has a plan. This is not that time.

This is time to say that the only one who hates this violence more than we do is God.

God was not absent from this event. God loves God’s creation, and in particular those members of creation in God’s own image—human beings. God was with each of those wounded and killed. I can’t say how, or if they knew it, or believed it, or cared. But from the perspective of the Christian faith there is no such thing as a God-forsaken person.

When evil intentions enter a room and snuff out life, what they don’t snuff out is the God of life who abides with those in the room more intimately that we can imagine.

St. Augustine taught us that God is closer to us that we are to ourselves. Psalm 139 teaches us that we cannot escape God’s loving presence. Nothing can change that.

God’s way of “fixing” is through human beings. In Advent, Christians prepare to celebrate the deepest mystery of our faith—the Incarnation, God’s unique union with humanity in the person of Jesus. Among other things, Incarnation means God is still with humanity and works through humanity.

I don’t believe in a deus ex machina—a god who swoops out of nowhere to fix things. I do believe in a God who works in, with, and through us—through the labors of those who have learned to love peace as much as God does, who have chosen to eschew violence in their own lives, and who work in small and large ways to end violence in our world.

This is some of what I decided to say in my rewritten sermon three years ago following the murder of innocent children in Connecticut:

At Christmas we will be remembering that God came as a weak, vulnerable child into our world.

And he came into this world, not another world, not a perfect world safe enough for a child God. He came into our world, a dangerous world. A world that has seen too many prayer vigils, a world that knows how dark the darkness can be, how deep the pain can go, how gripping the fear can become, how endless the grief. This is the world he entered as a child.

And we call this child the light, the light that shines in the darkness. And as hard as it is to believe sometimes, the darkness did not overcome him, and it has not, and it will not.

I would be willing to say that again.

The Rev. Dr. L. Roger Owens is associate professor of leadership and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and teaches courses in the MDiv, Doctor of Ministry, and Continuing Education programs. Before coming to PTS he served urban and rural churches for eight years in North Carolina as co-pastor with his wife Ginger. He has written multiple books including The Shape of Participation: A Theology of Church Practices which was called “this decades best work in ecclesiology” by The Christian Century.

2 thoughts on “God Isn’t Fixing This”