Earlier this academic year, Pittsburgh Theological Seminary’s American Religious Biography class studied biographical accounts of seven women and men whose lives spanned the centuries from the colonial era through the 20th century. After digging deeply into the historical accounts of those Christian figures, students reflected on what insight each narrative might have for modern Christians, asking What we can learn from the past to inform modern lives of faith? The blog below is the second in a four-part series of reflections by students in this course taught by the Rev. Dr. Heather Vacek. Read the previous reflections—Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter, Dream Is Freedom: Pauli Murray & American Democratic Faith, and Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America.

On June 17, 2015, Dylann Roof shot nine people gathered for a bible study at Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church in Charleston, S.C. Twitter blew up in the days after the Charleston shooting, as the public tried to make sense of this senseless tragedy. It became the place for ill-informed, anonymous users to post nonsense about who was really to blame for the Charleston Shooting. Conservatives blamed Planned Parenthood. Liberals blamed the National Rifle Association.

One educator had enough. Chad Williams, the chair of the department of African and Afro-American studies at Brandeis University, asked his Twitter followers to recommend books about American race relations using the hashtag #CharlestonSyllabus. Within 24 hours, the hashtag was trending on Twitter as educators, historians, and community activists, tweeted out their recommendations. Today the syllabus contains more than 500 books, blog posts, videos, podcasts, and lectures about race and Christian theology.

You can view the #CharlestonSyllabus online.

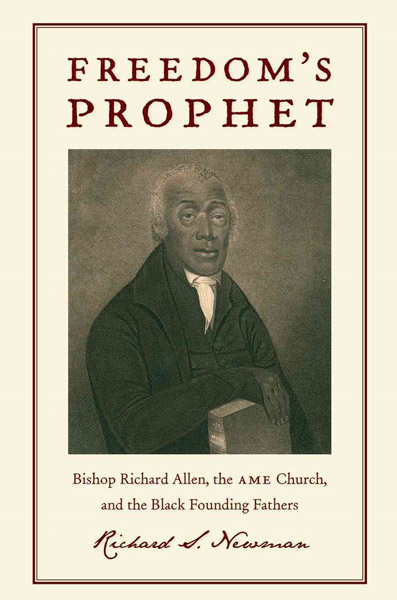

In a church history elective at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, we read one of the books on the Charleston Syllabus—Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers by Richard Newman. If we want to understand what happened in Charleston, S.C., we need to read the biography of AME founder Richard Allen. Newman argues that Richard Allen is a black prophetic leader because of his support of the American Dream, and liberation theology. The themes these ideologies illuminate—discrimination, liberation, and division—are the same themes that Americans struggle with today.

The American Dream is a cherished American idiom. The problem with the American Dream, in the 18thcentury as well as today, is that it usually only applies fully to white Americans. Allen believed that by working hard, learning a craft, and remaining humble, free blacks could rise in American culture (57). Allen struggled to reconcile his belief in the American dream with his experiences of racial discrimination. In fact, by as early as 1814, Allen became so disillusioned with American race relations that he began to consider colonization and emigration plans for African Americans (183).

In addition, Allen also experienced a disconnect between his belief in Christianity as a religion of liberation and his experience of racial discrimination. Allen read Scripture as an “Exodus typology” (Newman 162). The Exodus typology proclaimed that God desires to liberate his people from bondage. Sometimes, in order for blacks to participate in their liberation, they refused to accept white power (162-163). This lead to divisions within the Methodist church, culminating in the establishment of the AME Church in 1815.

What, then, can Allen’s biography teach the church about the Charleston shooting? Firstly, Allen’s biography gives us a sense of how deeply embedded racial discrimination is to the American way of life. If the American Dream applied only to whites, perhaps it shouldn’t be a surprise that a white person might feel as if they must violently protect an American Dream that excludes African Americans? Is it any wonder that a white Christian would? Secondly, Allen’s biography teaches us that Christianity both justified, and opposed, racial discrimination. Any liberation theology the church adopts moving forward will have to live in the tension of a faith tradition that, in practice, has both liberated and oppressed. Finally, Allen’s biography gives us a sense of how deeply divided the body of Christ is. For every person who believes that Richard Allen is a black prophetic leader, there may be a person who celebrates Dylann Roof as a protector of the American way of life.

The question of race and religion in America is a complicated one. But thanks to initiatives like the #CharlestonSyllabus, we can start to see that history unfolds in predictable ways. One of the reasons we read religious biographies is to see how faithful Christians of another era navigated the murky waters of Christian belief versus Christian practice, so that we too might faithfully discern how we might participate in Jesus’ mission for our world today.

All Citations taken from: Newman, Richard S. Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers. New York: New York University Press, 2008.

The full reading list for the Fall 2015 American Religious Biography course included: Catherine Brekus, Sarah Osborn’s World: The Rise of Evangelical Christianity in Early America (2013), John Wigger, American Saint: Francis Asbury and the Methodists (2009), Jon Sensbach, Rebecca’s Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World (2005), Richard S. Newman, Freedom’s Prophet: Bishop Richard Allen, the AME Church, and the Black Founding Fathers (2008), Matthew Avery Sutton, Aimee Semple McPherson and the Resurrection of Christian America (2007), Sarah Azaransky, The Dream is Freedom: Pauli Murray and Democratic American Faith (2011), Randall Balmer, Redeemer: The Life of Jimmy Carter (2014). In addition, readers interested in the role of history in the life of faith might enjoy: Margaret Bendroth, The Spiritual Practice of Remembering (2013).

Rebecca DePoe is a senior MDiv student at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.