I felt sheepish showing up to work on Tues., April 26 this year. I wasn’t wearing an oval American flag sticker boasting “I Voted” on my lapel—the one that has become the ultimate symbol of responsible citizenship. I had not voted and I wasn’t going to.

The fact is, I wasn’t allowed. Pennsylvania holds closed primaries, so as a registered Independent I’m not able to vote in them unless I join a political party, which I don’t plan to do.

Many years ago I heard the South African bishop and Methodist pastor Peter Storey, chaplain to Nelson Mandela while he was in prison and ardent opponent of Apartheid, warn pastors not to join political parties. The church, he said, needs leaders who are truly free, not beholden to a party platform or partisan agenda.

In other words: we need to be free from partisanship in order to be faithfully political.

The Church in Politics

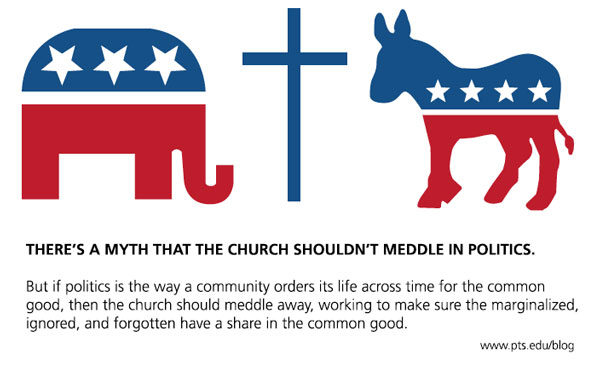

There’s a myth that the church shouldn’t meddle in politics. But if politics is the way a community orders its life across time for the common good, then the church should meddle away, working to make sure the marginalized, ignored, and forgotten have a share in the common good.

What the church shouldn’t be is partisan. Partisans confuse their identities with the agenda of a party. Christian partisans mistakenly believe that the mercy, peace, and justice—the shalom—of God’s Kingdom can be captured by the narrow agenda of a political party. And when this happens, as it often has, the results can be disastrous, especially for the church as it loses the integrity of its prophetic witness.

When my friends in North Carolina—former colleagues, professors, and church members—head to the capital building in Raleigh each “Moral Monday” to witness against what they take to be the damage the state’s ruling Republicans have done to the poorest and the most marginalized in the areas of voting rights, education, and discrimination, they are doing this not because they are partisan Democrats (many of them), but because they see that such policies don’t live up to God’s vision for a flourishing society. They are being political, not necessarily partisan.

As soon as the church becomes a spokesperson for a political party, it has lost its freedom to be faithfully political in a society that needs Christians guided by a Kingdom vision of human flourishing for all, rather than the narrow agenda of a party.

I remember in 2003 protesting at the beginning of the Iraq war. I joined friends from seminary in downtown Durham, N.C., a town where it wasn’t hard to find people willing to protest anything George W. Bush thought was a good idea.

I had a Mennonite friend other protesters tried to avoid; I wasn’t even sure how close I wanted to stand to him. He didn’t fit in. People stared at his sign in confusion. It read:

A Consistent Christian Ethic of Peace: No War, Racism, Abortion, Euthanasia.

A sign as unwelcome in North Carolina as it would have been in Oregon—how often does that happen?

My friend didn’t belong to any party’s camp. In a way, he was protesting with the protesters, but protesting against them as well as he stood up for what he believed to be a culture of life in the midst of a culture of death.

However you feel about his positions, one thing is clear: his political engagement was anything but partisan.

What can we do?

And in an election year, we need to remember that voting is not the only form of political engagement.

As the theologian Holly Taylor Coolman has recently written, “We need a fully-orbed account of political engagement. Political engagement involves elections and governance and law. It also involves service and solidarity and principled protest. It happens at the national level, the state level, and the local level. It is a conversation with the next-door neighbor.”

True conversation with the next-door neighbor is hard. It’s even harder when the conversation happens from partisan trenches. But such conversation, along with other forms of political engagement, are necessary for Christians who seek to foster the common good.

The Rev. Dr. L. Roger Owens is associate professor of leadership and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and teaches courses in the MDiv, Doctor of Ministry, and Continuing Education programs. Before coming to PTS he served urban and rural churches for eight years in North Carolina as co-pastor with his wife Ginger. He has written multiple books including The Shape of Participation: A Theology of Church Practices which was called “this decades best work in ecclesiology” by The Christian Century.

This is old PCUS and Lay Committee jargon. The Reformed tradition stresses the transformation of society. It is supremely political. The “kingdom of God” is not pie in the sky. It is a here and now demand. None of this pussy-footing around. The seminaries are not teaching sacrifice and risk for Jesus. Just careers in the particular variety of religion they espouse.

Heck yeah this is extalcy what I needed.