Radical is not a word often used to describe Fred Rogers. But his work in children’s television, and especially Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, was ministry ahead of its time. Almost 40 percent of seminary graduates today plan to use their degrees in contexts outside of the local church. Most who serve within the local church will have their preaching and teaching publicly accessible online because of pandemic shifts in congregational practice. The needs of ministry today could benefit from following the example of radically innovative Fred Rogers and his “neighborhood” congregation.

The Rev. Rogers

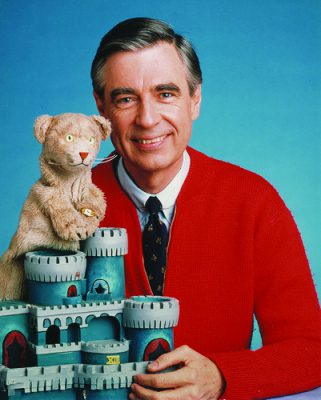

Outside of Western Pennsylvania and the Presbyterian Church, many people do not know that Mister Rogers is also the Rev. Rogers. He was an ordained Presbyterian minister and a 1962 graduate of Western Theological Seminary, a predecessor of Pittsburgh Theological Seminary. But learning this surprises few people. Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, a show that two generations of Americans grew up on, was deeply rooted in Christian theology.

“I think that my faith has affected everything that I’ve done, but that’s only natural; so have my genes,”[1] Rogers once said. Yet faith was hardly ever a part of the show, and even then, it was more implied than stated. That was an intentional choice by Rogers. “It’s far from denominational and far from overtly religious,” he explained. “The last thing in the world that I would want to do would be something that’s exclusive. I would hate to think that a child would feel excluded from the Neighborhood by something that I said and did.”[2]

Theology of the Neighborhood

Still, Christian theology was pervasive in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, and this concept of inclusion was perhaps the most recognizable throughout the years. Rogers testified to the dignity and worth of every human being with the guests on his show. He knew that representation matters, and wanted all children to see themselves in the show’s guests and characters.

Dignity and Worth

The Neighborhood welcomed people regardless of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or ability. Even before the recurring African American character Officer Clemmons was introduced in the famous episode about integration, many of the show’s guests were African American. Rogers blurred the lines of gender roles and stereotypes in a way revolutionary for the time, in his own words and actions as well as through guests and the characters in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe.

Storylines in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe also educated viewers about poverty and the challenges many people face to sufficiently provide for their children. And in one famous episode, Rogers welcomed Jeff Erlanger, a 10-year-old boy with quadriplegia, to sit and have a chat with him about what it was like to be in a wheelchair. A girl who used leg braces, Chrissy Thompson, was a recurring guest in the ’70s and ’80s.

With respect to race, gender, socioeconomic status, or physical ability, everyone was part of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. If viewers ever doubted this, Rogers would sing “I Like You as You Are” directly into the camera. The children watching couldn’t help but think he was singing specifically to them. Rogers once said:

“Christianity to me is a matter of being accepted as we are. Jesus certainly wasn’t concerned about people’s stations in life or what they looked like or whether they were perfect in behavior or feeling. How often in the New Testament we read of Jesus’ empathy for those people who felt their own lives to be imperfect, and the marvelous surprise and joy when they sensed his great acceptance.”[3]

Advocate or Accuser: Lessons from Seminary

Fred Rogers took eight years to graduate from Western Seminary, attending classes during his lunch break while working in television. His favorite professor was Dr. William Orr, who taught him that Scripture has an accuser and an advocate. The accuser, the evil one, “would like nothing better than to have us feel awful about who we are . . . and look through those eyes at our neighbor, and see only what’s awful—in fact, look for what’s awful in our neighbor,” said Rogers.[4] But Jesus, the advocate, he said, “would want us to feel as good as possible about God’s creation within us, and in [our minds] we would look through those eyes, and see what’s wonderful about our neighbor.”[5]

For Rogers, everyone was a neighbor. This biblical language of neighbor was so central to the show, even beyond the title. He called everyone—guests and viewers—neighbor, and treated them like one.

Beating Swords into Plowshares

In 1968, Mister Roger’s Neighborhood began airing nationally, just a few weeks after the Tet Offensive of the Vietnam War. The first week of the Neighborhood’s national broadcast focused on change. Lady Elaine Fairchilde makes changes to the Neighborhood of Make Believe. This leads a fearful King Friday XIII to establish border guards and wage war against any further change. But by the end of the week, Lady Aberlin and Daniel Tiger’s plan for peace and love wins over King Friday’s hardened heart. Throughout the week, Mister Rogers helps children understand how scary war can be, and how fear can lead to many different reactions. But war is not the only response to fear or conflict. Peace sometimes does prevail, and this is what Mister Rogers hopes for.

Fifteen years later, amid the nuclear escalation of the Cold War, Rogers again uses the Neighborhood of Make Believe to teach about war and the possibility of peaceful alternatives. Misunderstandings between King Friday’s Neighborhood and the neighboring Southwood leads to escalation of tensions, with King Friday planning to stockpile weapons. But eventually he realizes Southwood is planning to build a bridge, not start a war, between the neighborhoods, and peace is restored. The week ends with Mister Rogers singing about peace and quiet. Then the screen fades to the words of Isaiah 2:4:

And they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning forks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.

The program does not cite the prophet Isaiah, but Christians immediately recognize it as Scripture. This subtle use of Scripture is consistent with the message of the week and the Christian principle of peacemaking and pacifism.

Neighborhood Theology for Today

If Fred Rogers and his television ministry seems like it comes from an ancient time, that’s because it does. He grew up, and spent most of his working life, in a nation in which Christianity was far more central to culture than it is today in our post-Christendom context. But his willingness to pursue a radical new vocation of ministry—teaching theology in ways that a broader audience can understand and be included in—is a model perfect for today.

The Rev. Erik Hoeke is a writer at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and an ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. He will present a paper on Fred Roger’s Public Vocation of Ministry at:

The Rev. Erik Hoeke is a writer at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and an ordained elder in the United Methodist Church. He will present a paper on Fred Roger’s Public Vocation of Ministry at:

The Work of Fred Rogers: A Conference on his Context and Legacy, June 16-17, 2023, in Latrobe, Pa.

[1] Gladys Ford, “Creator of ‘Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood’ Relates His Faith to TV Production,” Pittsburgh Presbyterian, May-June 1985, 3, Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood Collection, 1955-2003, SC.1989.07, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System, quoted in Shea Tuttle, Exactly As You Are: The Life and Faith of Mister Rogers (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2019), 104.

[2] Fred Rogers, interview by Terry Gross, Fresh Air (radio), April 16, 1985, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1178498, 10:35.

[3] Fred Rogers, “Protestant Hour Broadcast Scripte” (radio, February 25, 1976, 2-3, FRA, quoted in quoted in Shea Tuttle, Exactly As You Are: The Life and Faith of Mister Rogers (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2019), 24.

[4] Amy Hollingsworth, The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers (Nashville: Integrity Publishers, 2005), 80.

[5] Ibid.